The history of trade between Australia and the islands just to its north goes back a long way. Trade largely defined the relationship between northern Australia and the island of Sulawesi and the city of Makassar in particular, for over 150 years. From the mid-18th century and possibly even earlier, sailors from Makassar crossed the Arafura sea each year to trade with indigenous Australians mainly for sea cucumber (trepang), pearl and turtle shell, which they then sold on to major markets in China and Japan. This trade continued until the early 20th century when border controls between the new Commonwealth of Australia and the Dutch East Indies made such trade no longer possible.

But in the 1930s Australians began to look outwards at the potential of nearby markets for their growing range of locally made products. Businessmen in Australia began to realise that the 70 million people in the islands to their north, ruled by the Dutch, were a potential market for their goods. Transport links were growing too, with the establishment in the late 1920s by the Royal Dutch Packet line (KPM) of regular passenger services between Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, and ports in Asia including Bali, Macassar (then spelt with a ‘c”) and Batavia, Singapore and Malaya. Two KPM sister ships, the Nieuw Holland and Nieuw Zeeland advertised as the “great white ships”, provided a luxurious liner service that was enjoyed by many Australians. Many other liners and cargo ships plied the Australia-Asia route in the 1920s and 1930s. Indeed, prior to World War II, Australians accounted for some 14 per cent of tourists to Bali, largely arriving on cruise ships.

The SS Nieuw Holland (sourced from http://www.ssmaritime.com/KPM-sisters.htm _)

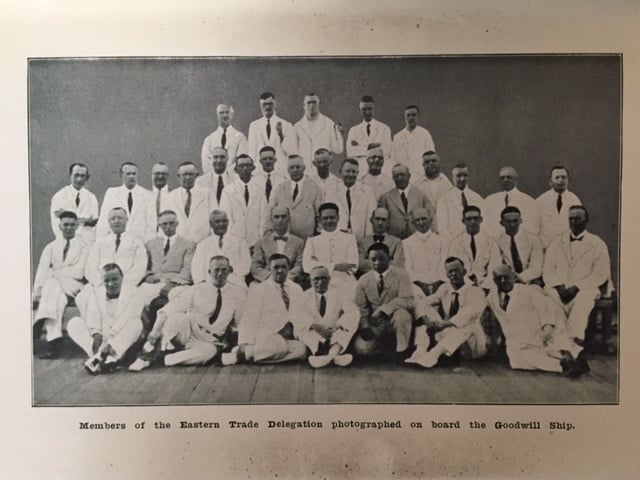

This is a fascinating if forgotten history, so I was delighted recently to come across a book that recounts what I believe to be the first trade delegation from Australia to what is now Indonesia. The book is titled The Cruise of the Goodwill Ship written by Australian journalist Richard J Moorhead, published by The Ruskin Press, Melbourne. In the somewhat flowery prose style of the day, the book relates the voyage aboard the SS Nieuw Holland of a delegation of 50 Australian businessmen with their wives and families, from Melbourne and Sydney to Macassar, Semarang, Chirebon, Belawan Deli in the Netherlands Indies, and thereafter to Singapore and British Malaya, and then back to Australia. The voyage took  place in April-June 1933, and was a private trade delegation sponsored by the Manufacturers’ Association of Australia. On board were also some Australian government officials.

place in April-June 1933, and was a private trade delegation sponsored by the Manufacturers’ Association of Australia. On board were also some Australian government officials.

As an account of Australian contact with the people of Makassar and Java it is illuminating. But reading this book you have to understand that attitudes were very different 86 years ago. Moorhead’s descriptions of the people he met and places he visited are characteristic of the views of white people of the day towards “native” populations. The world of the Netherlands Indies was three-tiered: at the top were the Dutch and other white races; in the middle were the Chinese, mostly traders; and at the bottom were the native races.

Despite the inherent paternalism in his writing, Moorhead clearly has affection for the Malays of the Netherlands Indies. He writes that everywhere the “Goodwill Ship” was received in with enthusiasm. The local welcome “literally took us by storm … and ran us off our feet.” (p.10) His enthusiasm for trade with the people of what is now Indonesia comes through many times throughout the book:

“What a market! What a challenge to us to press home in the immediate future the unique advantages our Goodwill Visit has thus so dramatically opened up for ourselves.” (p.95)

Moorhead writes that the ship’s first port of call after leaving Darwin was Makassar. He describes the moment the public came aboard: first came “droves” of Makassar school children “bright-eyed and smiling, and wearing sarongs resembling Scottish tartans, and headwear strongly suggesting the Glengarry cap” (a fair description of the traditional Bugis costume). Then came other members of the public, dressed in very colourful costumes that put the colours of the trade displays in the shade. One of the delegation members was keen to study the colours and styles of cloth required by local tradition so he could meet the needs of that market. After the public, some 500 local business people came aboard and started negotiating: sales of Melbourne millinery, dried fruit and other foodstuffs were made on the spot.

He regrets that “... none of our sales talk was in Malayan, the language of the seventy million ‘prospects’ we had come so far and at so much personal expense to captivate!” (p.10). We have heard a similar sentiment expressed in public in Australia again in recent times – even today not enough Australians can speak Indonesian.

The delegation was led by a hat maker from Melbourne, RF Sanderson, and also comprised sellers of Australian wine, brandy and dried fruit. Machine tool and car parts manufacturers and wireless manufacturers also had exhibitions on board the ship, as did dealers in fabrics, leather, soap, bacon biscuits, scents, fruit juices and dental products (according to a report in the SMH of 15 May 1933). Moorhead wrote that Australian flour and butter dominated the Netherlands Indies market (Australian wheat still dominates in the Indonesian market), and representatives from those two sectors accompanied the mission to boost sales. The greatest trade in each port was made in the foodstuffs, processed and unprocessed. South Australian wine got a good wrap and a consignment was ordered by the managers of a famous mountain resort hotel. But all regretted that there were no representatives from the wool growers and manufacturers associations, even though there was potential demand for wool products in tropical regions.

The delegation discovered that Japanese merchants had entered the Netherlands Indies in large numbers and were undercutting the prices of imported goods from Europe and Australia, particularly in textiles. Australia also faced regular criticism during port calls for its prohibition on sugar imports: at the time the Dutch permitted imports of Australian sugar.

Moorhead wrote a line that I could still use in my speeches and reports today:

“Macassar, besides being the Netherlands Indies port nearest to Sydney, is the capital of a rich island yet to be developed. The future prospects are decidedly of great moment to the Commonwealth.” (p.37)

Just replace Netherlands Indies with Indonesia. And spell Macassar with a “k”.

This trade mission went on to visit other ports around the Netherlands Indies, Singapore and Malaya. But their first stop was Makassar. And now we Australians are back here again.

The experiences of this private trade mission were widely reported in the Australian media in mid-1933, mainly through Moorhead’s own cabled reports. The success of this trade mission no doubt had significant influence on the decision of Prime Minister Lyons in 1934 to send Australia’s first official delegation to Asia, including Batavia, under the leadership of the Minister for External Affairs, John Latham. As a result Latham recommended that Australia establish Trade Commissioners in China, Japan and the Netherlands Indies. So in June 1935 the government appointed Charles Edward Critchley as Australia’s first Trade Commissioner to Batavia. Critchley set up an office in the Chartered Bank building in old Batavia and from September 1935 began operating Australia’s first permanent diplomatic representation in what was to become – a tumultuous decade later - the Republic of Indonesia.

***