We had been told to meet someone from the Pangkep District education department at the border between Maros and Pangkep districts on the main road north out of Makassar, then to proceed to a jetty at a place called Kassi Kebo. There we would take a 20 minute boat ride to Salemo Island for the launching of the “kelas perahu”, Pangkep District’s new initiative to bring middle-school lessons to the children of fishermen - a “school of the sea”. It sounded like a great idea, so I had agreed to join friends from the Australian Alumni Association in South Sulawesi (IKAMA) and the Institute of State Administration (LAN) to help support this.

We found the education department officials waiting for us at a warung and followed them to the jetty to be met by the Head of the Pangkep District Education Office, Pak HM Ridwan. Pak Ridwan apologised that the District Head (Bupati) of Pangkep had been “called away to Jakarta on urgent business” so he had been delegated to represent his boss. I liked Pak Ridwan – he was a former teacher like me – and clearly committed to the education of poor fisher folk.

We climbed into a heavy wooden perahu, navigating a motorcycle which had been tied onto the roof of the boat, and settled at the stern under an awning. The trip across a mirror-flat sea was punctuated by the occasional flying fish flying, and a few large splashings as a larger fish slammed into a school of smaller fish. We also passed strange, geometrically arranged lines of plastic bottles floating in the sea: plastic pollution self-arranging itself? No: it was lines of string held up by discarded water bottles with seaweed growing from them, a sideline for a local fisherman.

This sea is so fecund that it is not surprising that many of the 117 islands of the Spermonde archipelago are heavily populated. Fisher communities have occupied these islands for centuries – indeed, Salemo Island was one of the earliest settled islands in the Makassar Straits, and a regional centre of Islam. Important religious scholars had settled there and established a pesantren (Islamic boarding school) and one kyiai was reputed to have been able to walk on water from island to island to preach.

Today around 1,500 people live on Salemo’s one square kilometre, mostly fisher folk and their families. The pesantren is no more, but the island has a primary school, and a junior and senior high school. As the site for launching a new education initiative in the islands, I thought it was ideal.

When we arrived at the Salemo jetty it became clear that absent the Bupati, Pak Ridwan and I were the star attraction. We were welcomed by school children, first the boys doing a humorous welcome dance dressed up as old Malay men. Pak Ridwan and I were dragged into a circle of little dancing fellas and jigged and jogged along to the great delight of the crowd.

Then we moved on to witness the graceful dancing of the young teenage girls of the island, and it was lovely. All the proud parents crowded around as did lots of little kids; it was a total community event. TV cameras and journalists had arrived in a prior perahu and were filming us non-stop.

Pak Ridwan and I were then lead to a tent and seated in the VIP chairs (had the village headman lent them for the day?), and the formal ceremony began. In his speech Pak Ridwan explained the problem that faced teenage boys in fisher folk villages such as Salemo. Boys traditionally begin helping their fathers at sea from about 11 years of age. They accompany their fathers during the daily fishing trips – starting early in the morning and not returning until around 9.00am. Some have to accompany their fathers on extended trips away – up to two months at a time – to learn traditional skills such as navigating by the stars, how to find fish and sail their boats. They learn how to find such valuable delicacies as floating clumps of flying fish eggs.

Returning to the village, boys who have missed so much schooling are left behind: only about 53 per cent of fishermen’s sons carry on to junior high school. So Pak Ridwan’s assistant – Ibu Rukmini – came up with the idea of taking education to the boys at sea. Why not organise a kelas perahu, school of the sea, to provide books, lessons and study plans for the boys while they are away with their fathers? During these extended trips in particular, they often have much free time when they are fishing, so can use that time to study and try to keep up with their lessons.

I gave a speech applauding the initiative, saying this plan would help boys maintain their traditional skills as fishermen, while helping them keep up their school learning. I also noted that the Australian government was very pleased to have contributed towards education throughout the islands: 34 schools in four local sub-districts had been built to modern standards with Australian assistance.

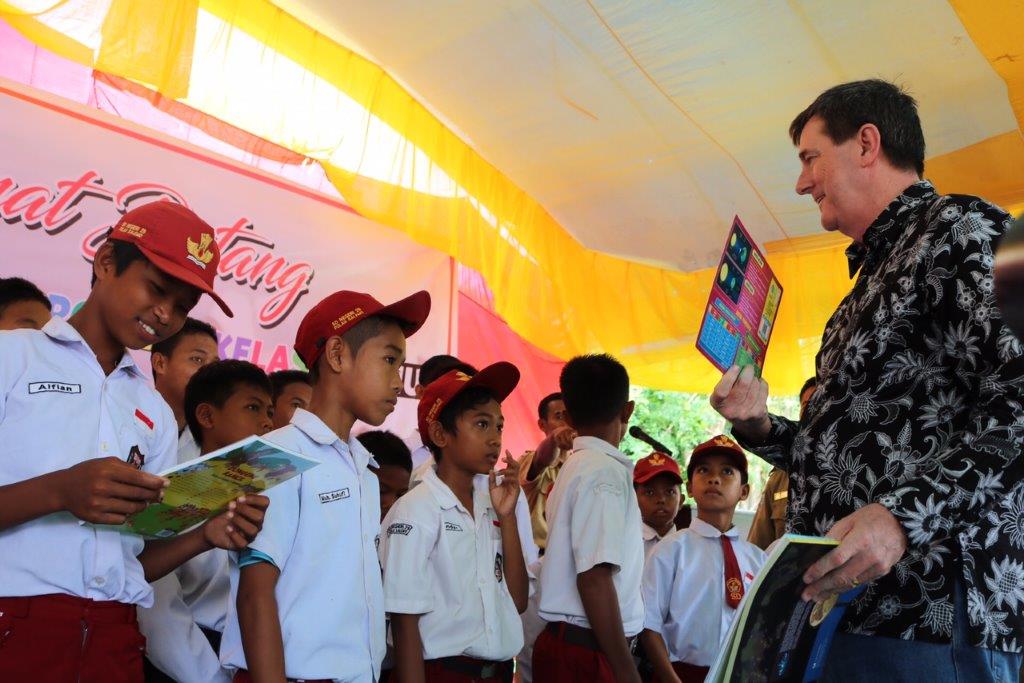

Then a group of the boys who help their fathers came on stage, and we handed out books. A book I had brought about sharks was popular, as were books about the stars and the planets. These kids are hungry for learning.

After the speeches children performed a range of lovely traditional dances, and also put on a play in the Bugis language about the kelas perahu initiative. It was very funny as they depicted a fisher family debating the benefits of taking books with them to sea. I said to Pak Ridwan that he will need lots of books – they would not last very long in fishing boats! And he should ask his boss for a dedicated school boat to visit the boys when they are out fishing with their fathers. He liked the last suggestion, but doubted the budget would go that far.

With the formal launching of the school of the sea over, we moved to a traditional Bugis wooden building on stilts, the house of the high school headmaster. On the floor of the front room were laid out dozens of plates piled high with freshly cooked crab, prawns, fish, rice and jackfruit vegetable soup. We sat on the floor and ate with our fingers, afterwards stretched out and relaxed on the veranda with Pak Haji, the headmaster.

Pak Haji had been teaching in Salemo since 1958: he was from the first generation of teachers in the new Republic of Indonesia who were given one year of training straight after high school and sent out to bring education to the largely illiterate masses. It was an incredible movement at the time, a story largely untold, which has helped move Indonesia into the modern age.

Pak Haji said that Salemo provided a great learning environment, devoid of the distractions and dangers of life in a big city like Makassar. Pak Haji, in his mid-70s and still teaching, had a point.

I left Salemo impressed by how strong a sense of community these islanders still have. The people of Salemo are maintaining their culture, dances, language and traditional way of life. And now with the kelas perahu initiative they have the possibility of seeing their sons get through high school too.

***